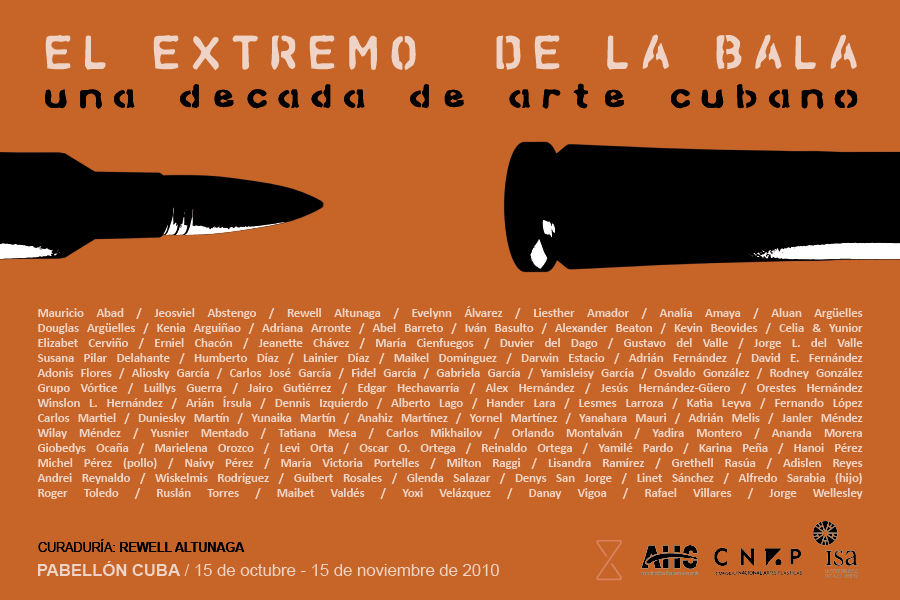

GROUP SHOW

“El extremo de la bala” A decade of cuban art

Date

October 15 – November 15, 2010

Artists

Abel Barreto, Adriana Arronte, Alberto Lago, Alex Hernández, Alexander Beaton, Aliosky García, Aluan Argüelles, Analía Amaya, Arián Irsula, Carlos José García, Celia & Yunior, Darwin Estacio, David E. Fernández, Dennis Izquierdo, Douglas Argüelles, Duvier del Dago, Edgar Hechavarría, Elizabet Cerviño, Erniel Chacón, Evelynn Álvarez, Fidel García (T10), Gabriela García, Gustavo del Valle, Humberto Díaz, Iván Basulto, Jairo Gutiérrez, Jeaneatte Chávez, Jesús Hernández, Jeosviel Abstengo, Jorge Luis del Valle, Kevin Beovides, Kenia Arguiñao, Lainier Díaz, Liesther Amador, Luillys Guerra, Maikel Domínguez, María Cienfuegos, Mauricio Abad, Osvaldo González, Orestes Hernández, Rewell Altunaga, Rodney González, Susana Pilar Delahante, Winslon L. Hernández

Curated by

Rewell Altunaga

Gallery

Pavilion Cuba

Location

Havana, Cuba

Curatorial Statement

The world, as we have known it throughout history, has definitively changed.

Reality is increasingly less historical and more immediate. We are trapped in a web of information and images that induces us to accept the medium in which we live as a grand myth, growing ever more distant from its origins. The “end of history” has been proclaimed. Today, fiction after fiction emerges, rendering the meanings of the past obsolete; over time, what once happened becomes categorized as invented. History has become a literary genre¹. The past and the present languish before a co-historical and media-driven stage, where the kidnapping, struggle, and liberation of a president can be seen with the same dramatic intensity as the highest-grossing fictional films. This is the era of reality shows and real-time; we are all characters, and the future is being shaped.

The thought of the 21st century cannot mirror that of the old millennium. It is governed by new structures, paradigms, and disappointments. The first-world super-soldiers of this decade go to war guided by GPS, listening to digital music soundtracks, in an epic or dramatic scene they capture with video cameras—mounted on their helmets or rifles—and later upload to YouTube and link to their blogs. They entertain themselves. Young people “play” these same wars on hyper-realistic interfaces, with Hollywood-like scripts that depict a hegemonic and distorted version of history. They record their videos and upload them to the web. They entertain themselves². Meanwhile, the planet convulses with natural disasters, economic crises, armed conflicts, and terrorism; we dance to tech-tonik, reggaeton, and techno-cumbia. We consume faster, more versatile, more banal, and less meaningful images. We approach what is called the “high definition” of the image: the greater the absolute definition and realistic perfection of the image, the more we lose the power of illusion³.

The illusions of this generation are the same as those of the previous ones. We are neither less committed nor less daring; we simply exhibit a (logical) change in attitude. We have been shaped by poor examples. We live in a period marked, above all, by new social, political, and aesthetic stances. Today, new communication mechanisms shrink the Earth and produce a homogeneous, less impressionable society. In a planet oversaturated⁴ with images and information, the analysis of what is transcendently human is left behind⁵. We harbor new illusions but do not cling to them; we are detached, skeptical of old axioms. We are not interested in “living to die” but rather in “dying to live.” We still carry the enthusiastic pessimism⁶ that humanity bore in the last century. The dust and stones stained by millennia of war and lies have left us with great skepticism. We are a generation that must learn not to succumb, not to self-immolate, and to establish an intrinsic struggle against ego and vanity. Contemporary thought must rediscover optimism. The battle must increasingly take place silently—in our minds, in our senses.

Globalization processes, accelerated by the proliferation of social networks and online communities, demonstrate that conservatism has been rendered obsolete in the face of relentless cognitive permutations. These teach us that diversity must be the ideology of the future and that cultural contagions (this time without antidotes) point to a coherent holism where we share and apply systems of thought and practices from anywhere on the planet—or perhaps they lead us to arbitrary chaos, where anyone with a small electronic device can articulate reckless ideas that gain attention globally, bypassing ethical or aesthetic filters. It is the responsibility of those of us working in the cultural field—artists, intellectuals, and those involved in art institutions—to act as guides and spiritual shamans in a world governed by visuality and information.

The already historical postmodernity revealed to us an incipient and fragmented pluralism, organized around neo-trends and post-movements and structured by terms that set limits on the hybridizations preceding the current cultural period. In this period, historicist references to immediate reality intersect with social and media fictions. Contemporary art reflects this hyper-pluralism—not only in genres but also in themes and concepts—appropriating, through new communication and information media, the most diverse cultural substrates, forming an increasingly homogenized network despite its evident variety.

If, in the past century, artistic production could be defined with some clarity by geographic zones—even during the height of diversity in the last two decades, when “everything was valid,” recognizable aesthetics such as Caribbean, Latin American, African, Asian, or European art still emerged (art history books would list them in reverse)—today’s visual practices aim toward territorial undefinedness. Artists create works that are increasingly less local or, at least, exhibit no evident signs of originality or identity. Beyond superficial codes and cultural stereotypes, these works attempt to engage in dialogue based on the essential premises underlying all artistic creation.

Art is dying once again. The current global crisis does not affect it; art appears immune—a bubble that grows daily, the final neoliberal stronghold. The gluttony of a consumerist society is returning art to its old spirit of modernity, rising over the illusory corpse of the fleeting postmodern period. We increasingly fail to discern what we seek within contemporary art; even poetry is becoming an exhausted resource.

Artistic creation must assume the responsibility of making the social processes of the contemporary world poetic and reflective. As an effective means of social transformation, it must proliferate lines of resistance against existing forms of power. Rather than seeking their overthrow, it must subvert and parody preconceived aesthetics, inducing reflection through socialization. Current communication and information media—new elements of consumption—are not merely objects or tools; they are integral to the very structures of living and meaning-making. Modern technology does not merely assist in living; it becomes the space where life unfolds—a new battlefield for cultural and ideological conflicts.

In this sense, I do not believe in a “return” to aestheticized art or a “resurgence” of politics in art. Speculation has arisen about the comeback of abstraction, the supremacy of video, or the resurgence of painting—among other supposed regressions of stances, trends, and genres—but these simply reflect a coexistence that has persisted all along. This reconfiguration, not exclusive to the art world, demonstrates that contemporary societies must aspire to an integrative globalization rooted in genuinely human sensitivity. Art, from the highbrow to the popular, is also a weapon that must be learned and taught—just as our predecessors did. This time, however, the battle is not against other humans but for humanity itself.

References:

1 Casares.

2 “The video game industry has, for years, vastly surpassed cinema and other art forms in terms of production and consumption.”

3 Baudrillard, Jean. La ilusión y la desilusión estéticas.

4 Virilio, Paul. La ciudad sobreexpuesta.

5 “The modern metropolis, neo-geological, like the ‘Monument Valley’ of some pseudo-lithic era, is a ghostly landscape, the fossil of past societies whose technologies were intimately tied to the visible transformation of matter, a project from which sciences have increasingly distanced themselves.” Virilio, Paul, La ciudad sobreexpuesta.

6 Ortega Campos, Pedro. Notas para una filosofía de la ilusión.

Rewell Altunaga

Havana, December 2010